welcome to the lewistown circuit

third district of the african methodist episcopal church

FROM SADDLE TO SANCTUARY: THE RISE OF AME CHURCHES IN CENTRAL PENNSYLVANIA

Our Methodist Roots

-

The story of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church begins with the larger movement of Methodism.

Methodism began as a renewal movement within the Church of England in the early 1700s, led by John Wesley and his brother Charles Wesley. While studying at Oxford University, they formed a “Holy Club” focused on prayer, Bible study, and acts of service—earning them the nickname “Methodists” for their methodical spiritual discipline.

John Wesley’s powerful preaching, practical theology, and organizational genius helped spread the movement across Britain and colonial America, particularly through field preaching and the work of itinerant ministers (later called circuit riders). By the late 1700s, Methodism had grown into a global movement, emphasizing personal holiness, social justice, and salvation for all.

-

Circuit riders were traveling preachers who spread Methodism across the American frontier in the 18th and 19th centuries. Often on horseback and carrying little more than a Bible and a saddlebag, they rode long distances—through mountains, farms, and small towns—to preach, baptize, marry, and plant churches wherever people would gather.

Organized by leaders like John Wesley and Francis Asbury, circuit riders were the backbone of early Methodism, especially in rural areas with no established clergy. They faced harsh weather, isolation, and exhaustion, yet they helped build a movement rooted in accessibility, adaptability, and deep personal faith.

Their legacy lives on in how the church still values connectional ministry, shared leadership, and bringing the gospel to where people are.

-

One of the most consequential conversions in American religious history happened when a white Methodist circuit rider, Freeborn Garrettson, visited a plantation in Delaware around 1777 and preached against slavery. Among the enslaved listeners was Richard Allen, who later wrote that Garrettson’s words convicted him of sin and awakened his soul: At the age of 17, Richard was converted: “all of a sudden my dungeon shook, my chains flew off, and glory to God, I cried. My soul was filled. I cried, enough for me--the Saviour died.” Allen would go on to purchase his freedom, become a lay preacher, and later an ordained minister in the Methodist Episcopal Church.

🤝 A Partnership with Francis Asbury

As Allen’s preaching reputation grew, he drew the attention of Francis Asbury, the pioneering bishop of American Methodism. Asbury recognized Allen’s talent and commitment, and for a time, Allen traveled with Asbury as an itinerant preacher, sometimes walking dozens of miles between stops. Though Allen was not yet ordained, Asbury invited him to preach at services, especially when reaching African American audiences.

This relationship opened doors—but also revealed the limitations of the white-led Methodist Episcopal Church. Even as Allen preached revivals that converted hundreds, he was often denied pulpits in white churches or was relegated to preaching at 5 a.m., when white members would not be inconvenienced.

The Walkout That Launched a Movement

-

Allen eventually settled in Philadelphia, where he was permitted to preach early morning services at St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church, one of the city’s oldest Methodist congregations. He helped build up a large and devout Black membership through his preaching, pastoral visits, and leadership. Within a few years, Black congregants made up a significant portion of the church community.

But that growth brought resistance from white leadership.

Without warning or discussion, the trustees of St. George’s built a segregated gallery and ordered all Black worshippers to move upstairs. When Black leaders, including Absalom Jones, knelt in their usual place for prayer, they were forcibly removed in the middle of the service.

-

In response, Allen, Jones, and other Black members walked out, never to return. That moment—an act of nonviolent protest inside a sacred space—would reshape American religious history.

In 1787, shortly after walking out of St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church, Richard Allen and Absalom Jones co-founded the Free African Society (FAS). It was one of the first mutual aid societies organized by and for free African Americans in the United States. Though not originally a church, the society was deeply spiritual in vision and modeled on early Christian community principles.

The Free African Society aimed to:

Support the sick, widowed, and orphaned

Provide burial assistance

Promote moral discipline and religious piety

Uplift the social and spiritual life of free Black people

Its members pledged to assist one another in times of hardship and to build an ethical, self-sustaining Black community. They met regularly for prayer, Bible reading, and discussion—laying a spiritual and organizational foundation for later church formation.

-

As the Society grew, so did the desire among members to worship freely without segregation or oversight from white religious authorities. Over time, theological and denominational differences among members led to the formation of distinct Black congregations:

Absalom Jones helped establish the Episcopal African Church of St. Thomas

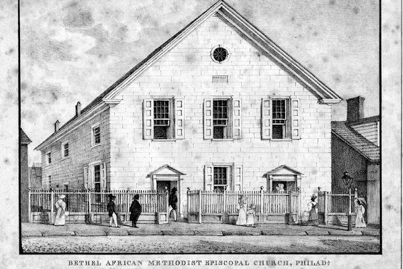

Richard Allen led the founding of Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, which would become the mother church of the AME denomination.

The Free African Society thus served as the bridge between protest and institution—a vehicle that carried Black Christians from exclusion to self-governance, from mutual aid to ministry.

The AME Church’s Foundation of Justice and Faith

-

Allen and his followers began worshiping independently, first in homes, and later in a repurposed blacksmith shop, which they named Bethel Church. Despite their clear intention to self-govern, white Methodist officials continued to challenge their right to operate independently, attempting to control the property and clergy appointments.

In 1816, the dispute reached the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of Allen and his congregation. The court recognized that they had the right to organize independently, govern themselves, and appoint their own clergy. This legal victory paved the way for the formal establishment of the African Methodist Episcopal Church—the first independent Black denomination in the United States.

The ruling not only affirmed the congregation’s property rights; it validated the broader principle that Black people could lead, structure, and sustain their own religious institutions—without interference or paternalism.

What began with an act of protest at the altar became a movement of liberation—a church grounded in faith, justice, and Black leadership.

-

That same year, Allen convened other independent Black congregations from across the mid-Atlantic. Together, they founded the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, electing Allen as its first bishop. It was the first denomination in the United States founded by and for people of African descent—an act of faith, freedom, and spiritual self-determination.

From his early days traveling on foot with Francis Asbury, to his firm stand for justice in Philadelphia, Richard Allen forged a path that blended evangelical zeal with structural liberation. The AME Church he founded would go on to plant churches across the nation, send missionaries abroad, and support abolition, education, civil rights, and community empowerment.

-

In 1816, Allen and delegates from several Black Methodist churches formed the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first independent Black denomination in the United States. Allen was elected and consecrated our first Bishop. Though the AME Church retained Methodist theology and polity, it built upon a new foundation: Black leadership, autonomy, and liberation.

That same year, Allen convened other independent Black congregations from across the mid-Atlantic. Together, they founded the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, electing Allen as its first bishop. It was the first denomination in the United States founded by and for people of African descent—an act of faith, freedom, and spiritual self-determination.

From his early days traveling on foot with Francis Asbury, to his firm stand for justice in Philadelphia, Richard Allen forged a path that blended evangelical zeal with structural liberation. The AME Church he founded would go on to plant churches across the nation, send missionaries abroad, and support abolition, education, civil rights, and community empowerment.

the lewistown circuit: ministry in the mountains

-

Circuit riding remained at the heart of AME expansion. Itinerant preachers brought not only scripture, but education, advocacy, and institution-building into communities, especially in rural and mountainous regions where free people often lived in isolation.

The Allegheny corridor of central Pennsylvania—including Mifflin, Huntingdon, Blair, and Centre Counties—was home to one such circuit: the Lewistown Circuit, documented as early as 1834. This circuit included key congregations that would serve Black residents through faith and fellowship.

-

In the 1830s, the Lewistown Circuit emerged as a vital spiritual route within the African Methodist Episcopal Zion (AMEZ) Church, spanning multiple rural communities. Rev. David R. Stevens served as elder of this circuit, which included Lewistown (Mifflin County), Nippenose Township (Lycoming County), Northumberland (Northumberland County), and Bellefonte (Centre County).

By 1834 the Lewistown Circuit was in the hands of the AME Church and served by pastors such as Rev. Garner, Rev. Wayman, and Rev. Shorter.

-

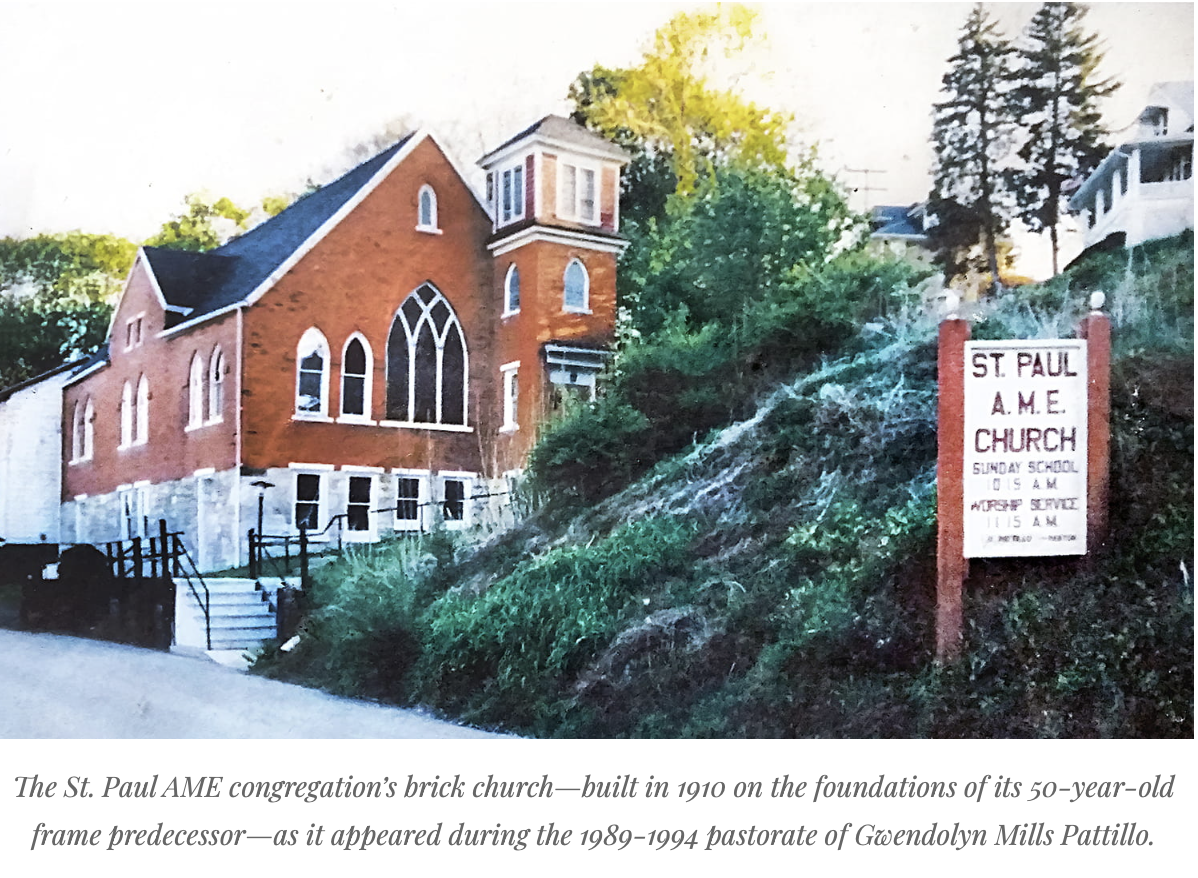

Though the days of horseback preachers are behind us, the circuit model remains vital in the AME Church—especially in rural areas like central Pennsylvania. Today, a circuit includes the Bethel AME Church, Lewistown, Bethel AME Church, Mt. Union, and St Paul AME Church, Bellefonte.

Under the visionary leadership of Bishop Stafford J.N. Wicker, the Third Episcopal District is renewing its commitment to legacy and presence. Bishop Wicker affirms that every church matters, and that our sacred spaces must be preserved by us.

Reviving the historic Lewistown Circuit, Bishop Wicker has entrusted the work to Rev. Dr. Renita Marie Green, supported by Rev. Sylvia Morris.

Together, they are reclaiming historic ground, reconnecting congregations, and reimagining ministry for today—ensuring the AME legacy continues to shine where it first took root.